Hypothesis---why do neutralizing antibody titers max out?

In the last post, I conjectured that the maximum possible neutralizing antibody titer against viruses in humans is around $2^{14}$. In this post, I’ll present a simple model of how immune response relates to viral infectiousness and highlight some surprising connections it explains.

This is the third in a series of “Night Science” posts about how the immune system works, from the point of view of someone who thinks a lot about the impacts of immunity on human infections but has a very incomplete and idiosynchratic knowledge of immunology. As explained in this post, my goal in sharing this kind of thing is to show multiscale thinking in action—what does it look like to make quantitative connections across domains, with an eye toward thinking more clearly about how biology and epidemiology interact? Anyway, enjoy!

Previous posts in the immunity theory series

Prelude: let’s look closer at the polio immunity model

In re-reading the key reference on poliovirus immunity from my former colleague, Matthew Behrend, that was the starting point for everything I know about viruses and immunity, I found a citation to a paper from 1984 defining the Immune Response profile model that is a more thorough version of the next few sections but based on flu instead of polio!1 After the initial sting of “OMG I’ve never had an original idea” passed, how cool is that?! It’s great in science to realize others see what you see and have additional data you’ve never seen to prove it.

Poliovirus Neutralizing Antibody Response model

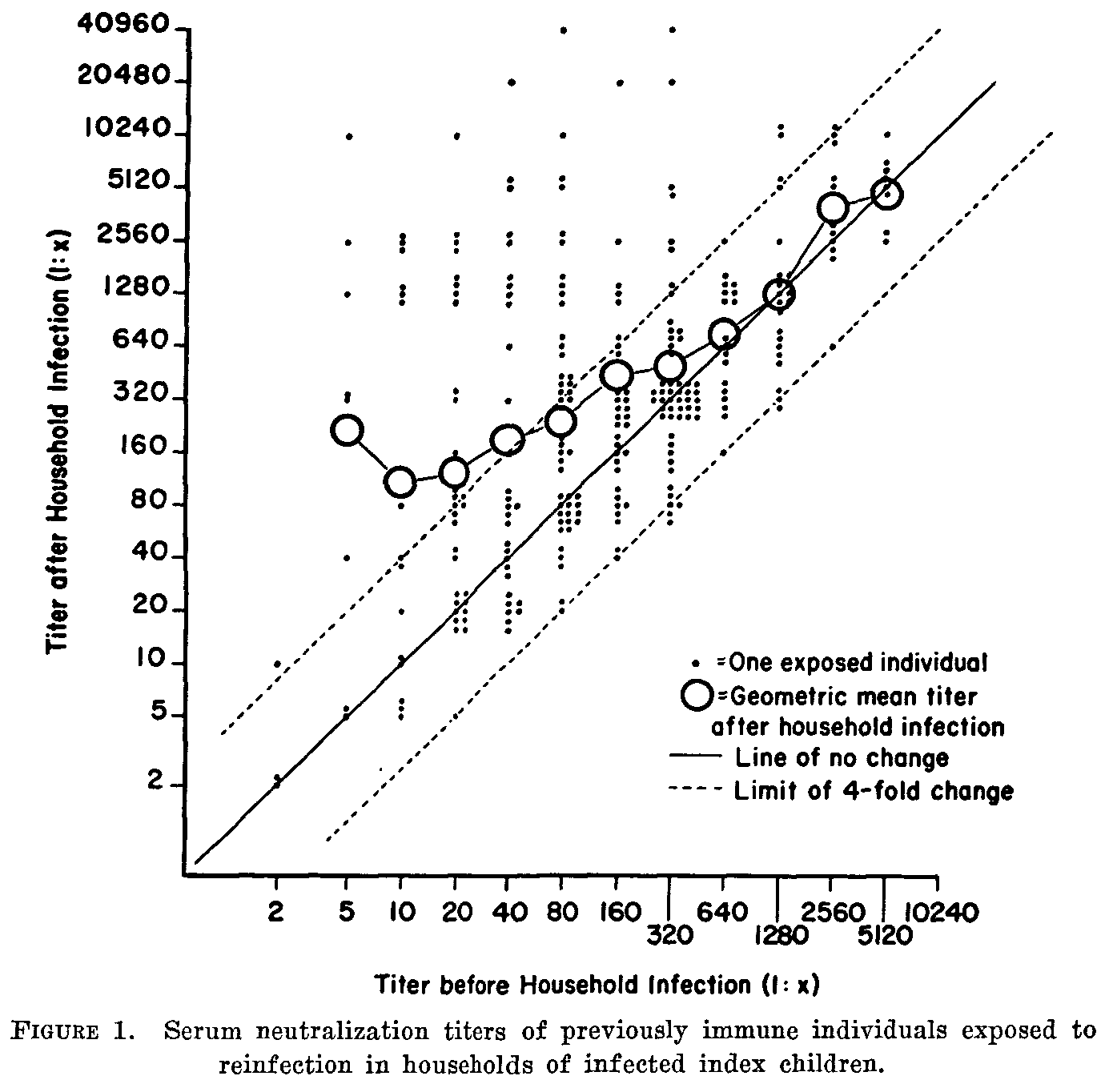

In the last post, I showed this lovely figure from this 1957 paper with pre- and post-infection antibody titers for poliovirus that tells us everything we need to know about neutralizing antibody response after poliovirus infection.

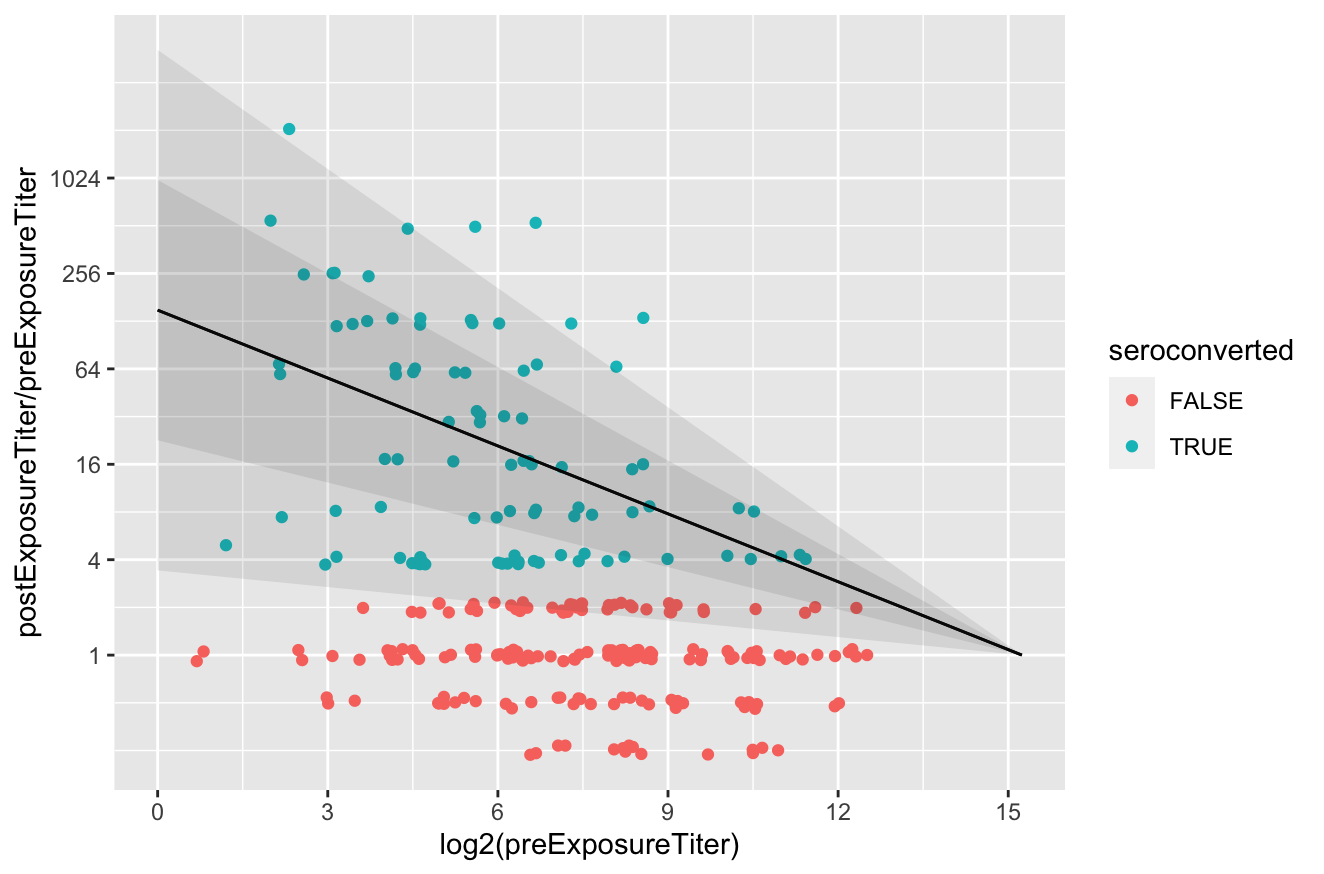

Now, let’s look at the actual immune response model we derived from it (described in the supplement to this paper).2 Here is the same data, plotted in terms of the post-pre-ratio vs pre-infection titer and jittered for visibility, with the response model overlaid:

The people who are not “seroconverted” show no signs of poliovirus infection within the pre-post interval and so they show the assay variability.3 The fitted response model shows the mean and one- and two-standard-deviation prediction intervals for the immune response, with the assay variability removed. The model is defined as

The people who are not “seroconverted” show no signs of poliovirus infection within the pre-post interval and so they show the assay variability.3 The fitted response model shows the mean and one- and two-standard-deviation prediction intervals for the immune response, with the assay variability removed. The model is defined as

and

\[\text{sd}\left[\log_2(\text{post-challenge titer})-\log_2(\text{pre-challenge titer})\right]=\sigma_0\left(1-\frac{\log_2(\text{pre-challenge titer})}{\log_2(\text{max titer})}\right)\]The best fit parameters are $\mu_0=7.2$, $\sigma_0=2.9$, and $\log_2(\text{max titer})=15$.

(As an aside, you might be asking yourself, didn’t he say $2^{14}$ and not $2^{15}$? Yes, well. First, see footnote 11. Second, rooted deep in memory was actually the observation from this earlier model derived from an independent metastudy led by the aforementioned Matthew Behrend, where the average max titer across all serotypes and vaccine formulations is $2^{13.5}$. So anyway, $2^{14}$-ish and with slight embarrassment.)

Model: titers max out because you can’t respond if there’s no infectious virus

The observation that titers max out at the same place in mean and variance tells us that, with sufficiently high pre-existing antibodies, there is no new adaptive immune response if you were to somehow get infected.

How could you have no adaptive immune response if you somehow got infected to a pathogen that you have a huge amount of memory immunity to? Pre-existing neutralizing antibodies provide passive protection. They circulate in your body, perfuse your tissues, and bind viruses as they encounter them. So a simple model of how to get no immune response to infection at high titer is the following: if the concentration of neutralizing antibodies is high enough, every virus produced by an infected cell will be neutralized and prevent any spreading to the next cell. At the max titer, infections cannot propagate and non-live vaccines are rendered inert.

The simplest model for the response is that the post-infection titer is linearly proportional to the pre-infectious titer times the dose of viable virus you receive.

\[(\text{post-challenge titer}) = \text{c}*(\text{viable dose})*(\text{pre-challenge titer}) \tag{2}\]where $c$ is the constant of proportionality. This simple model assumes that new adaptive responses are independently built on top of pre-existing immunity, and that the more pre-existing immunity you have, the larger the new response will be, in proportion to the viable dose leftover after the passive components of pre-existing immunity do their thing. So if neutralizing response can shrink the viable dose down to $c^{-1}$, then there is no new response. Interestingly, we’ve known that this model relating post and pre titers is plausible, at least for the fixed dose given by an inactivated vaccine, going back to at least to Jonas Salk (where he described log-post-over-pre is proportional to log dose). But how could this apply to replicating infectious virus? And does it make sense for the limit to be $c^{-1}$ and not zero viable dose? What’s $c$?

When we look at what we know about poliovirus infectiousness in humans and antibody titers, we see something super cool

What is the relevant viable dose at the start of a polio infection? Well, each infected cell makes about 900 infectious units per replication cycle (one source of many). So, in the absence of any prior immunity, the viable dose should be about 900. But, as described in the first post in this series, we know from human challenge studies that only 1 in 33 of the typical poliovirus infectious units cause infection in an unimmized person, and that the dependence of the probability a cell culture infectious unit is infectious in a person with pre-challenge neutralizing antibody titers looks like

\[\bar{r}_{\text{pre-challenge titer}}=\frac{1}{1+\frac{\beta}{\alpha}(\text{pre-challenge titer})^{\gamma}}\]with $\alpha=0.44$, $\beta=2.3$, and $\gamma=0.46$ for wild poliovirus (source). So the viable dose shed by each infected cell in a person is roughly $900\bar{r}_{\text{pre-challenge titer}}$, and our simple immune response model is

\[(\text{post-challenge titer}) = \text{c}*(900\bar{r}_{\text{pre-challenge titer}})*(\text{pre-challenge titer}) \tag{3}\]Something remarkable is that Equation (1) and Equation (3) are the same thing! Take logs and see:

\[\begin{align} \mu_0\left(1-\frac{\log_2(\text{pre-challenge titer})}{\log_2(\text{max titer})}\right) &= \log_2(900c)-\log_2\left(1+\frac{\beta}{\alpha}(\text{pre-challenge titer})^{\gamma}\right)\\ &\approx \log_2(900c)-\log_2\left(\frac{\beta}{\alpha}(\text{pre-challenge titer})^{\gamma}\right) \\ &= \log_2\left(900c\frac{\alpha}{\beta}\right)-\gamma\log_2(\text{pre-challenge titer}) \end{align}\]Equating terms, we see first that we should have

\[\frac{\mu_0}{\log_2(\text{max titer})}=\gamma \tag{4}\]relating our model derived from antibody response and our model derived from susceptibility to infection. The remarkable thing is $\gamma=0.46$ and $\frac{\mu_0}{\log_2(\text{max titer})}=0.48$! I’ve been lazy and not showing uncertainty intervals, but this is damn near exactly the same, and very much not significantly different with the intervals that I have!

I want you to share in my excitement. We get the exact same model, with the exact same numbers, from two very different places. The first is from just directly measuring adaptive immune response. The second is from fitting a model to human challenge studies for the probability a person gets infected from a range of oral doses,4 taking seriously the biological interpretation of the model in terms of the human infectiousness per cell culture infectious unit, and finding empirically via this agreement that pre-challenge neutralizing antibodies have exactly the same effect on both getting infected and building new responses to prevent the next infection. And the assumption that ties them together is that this all is determined by what happens during the viral replication and propagation process at the cellular level!

Second, let’s think about what the minumum viable dose is, below which there is no immune response. We can now estimate that constant $c$ with

\[\mu_0 = \log_2\left(900c\frac{\alpha}{\beta}\right) \tag{5}\]Solving for $c$ using wild poliovirus $\mu_0$, $\alpha$, and $\beta$, we find $c=0.9$, and the minimum viable dose at max titer is 1.1.

This is exactly as it should be! At the maximum titer, every infected cell, starting from a single infectious unit, can only make 1 more infectious unit. We have have found the point at which the effective reproduction number of viruses between cells is 1! Below that, infections cannot grow exponentially and will die out quickly. No exponential growth, no persistence, no new adaptive immune response! It’s all self-consistent!

How cool is this?!

I want to reiterate again how awesome this is. From models of data about the probability people will get big, obvious polio infections, and from models of data about how peoples’ immune systems respond—coarse models of organism-sized things—we’ve been able to derive how both are governed by what happens at the level of a single virus interacting with a single cell and the neutralizing antibodies perfusing the interstitial space immediately around that cell.

Furthermore, the macroscopic, person-scale models are remarkably simple. The immune response model is a simple, continuous function that holds across the entire range of achieveable antibody-mediated immunity. From the first infection in a completely naive person, to the highest possible memory response. All of the enormous complexity of the antibody-mediated immune system exists to do one simple thing defined in Equation (2)–linearly increase your neutralizing antibody response in proportion to how much you already have and how much pathogen gets through it. And susceptibility is all about the dose, and how much of that dose gets through the immunity. And the complex physics reduces to simple, first-order chemical kinetics with a fudge factor for how getting antibodies and viruses to run into each other is hard (sub-diffusive).

And, as I argued in the last post, this appears to be fairly universal for acute viral infections in people. As shown in Equation (4), the max titer is only a function of how antibodies transport through tissue (represented by the $\gamma$ and discussed in the first post and the maximum achieveable active dose (particles + infectiousness or antigenicity in the case of an inert vaccine) at the scale of a single cell and the immediately surrounding extracellular environment and antibody trafficking through it.

Next post

In the next post, I think I’ll talk about how we can bravely over-interpret Equations (4) and (5) to better understand vaccine dose finding, see if we can understand conditions by which max titer can vary, and maybe say some stuff about what if antibodies were different sizes.

Or maybe something else. I’m excited to commit this unedited and feeling a bit jumbled and excited now. Anyway, enjoy and please comment if you like, don’t like, have questions, or see something confusing!

For attribution, please cite this work as:

Famulare (2024, Mar 18). Hypothesis---why do neutralizing antibody titers max out? Retrieved from https://famulare.github.io/2024/03/18/Hypothesis-why-do-neutralizing-antibody-titers-max-out.html.

The script used to generate various numbers in this post can be found here.

-

but unfortunately the numbers aren’t directly comparable because it’s based on hemagglutinin assay inhibition titers and not neutralizing antibody titers. Different reference standard. ↩ ↩2

-

To my eternal shame, we fit the mean and variance separately in the paper even though we knew they should’ve been coupled. In my defence, I was very frazzled at the time by intense overwork on the Seattle Flu Study and Wes had no help debugging what I now suspect was a subtle convergence error in the fitting script when he tried to do it right. The figures and parameters mentioned in this post differ from the paper because I redid the analysis correctly here. ↩

-

except you might notice that at very high titer, some of the non-responder dots are inside the range of expected responses. At very high titer, responses are small enough that you can’t tell from seroresponse if someone was infected in the interval or not. This should be accounted for in how I fit the model, but I was too lazy to do so. Which also means the max titer is likely biased a bit higher than the real value. Or closer to $2^{14}$ :-). ↩

-

As an aside, I started my deep dive because I couldn’t make sense of the susceptibility dose response part of the original model in the Behrend paper, and so I re-did it my own way (and found the original was wrong but for reasonable reasons). In going down that road, I’ve since redeveloped a bunch of other stuff, but I periodically find myself surprised at everything Matthew thought about, wrote about, got right, and I forgot! ↩