Conjecture---the maximimum possible neutralizing antibody titer

Here’s a conjecture for you: the maximum possible neutralizing antibody titer against any virus in humans is around $2^{14}$ aka $10^{4.2}$ aka $16,000$.

As in, whenever you measure neutralizing antibody titers to a pathogenic virus, no matter how many times a person has been immunized against that pathogen, you’ll find the highest titer you ever measure is around $2^{14}$. This is both a statement about some approximate biological universality that is very surprising (at least to me!) and says a lot about how immune responses work, if only we can decode what it means.

In the rest of this post, I’ll lay out some choice evidence, and discuss some of the “but wait how can this make any sense?”s. And remember, this is a blog post. This is Night Science. I’m hoping to spark curiosity and a discussion. I’m hoping I’m right and someone out there runs with it. And I’m hoping if I’m wrong someone will see this and tell me why. Point being, I’m hoping for connection.

This is the next in what is looking like a series of “Night Science” posts about how the immune system works, from the point of view of someone who thinks a lot about the impacts of immunity on human infections but has a very incomplete and idiosynchratic knowledge of immunology. As explained in this post, my goal in sharing this kind of thing is to show multiscale thinking in action—what does it look like to make quantitative connections across domains, with an eye toward thinking more clearly about how biology and epidemiology interact? Anyway, enjoy!

Previous post in the immunity theory series

The evidence

Polio

As is so often the case for me, it all starts with polio. Polio is the best model system in infectious disease because it contains everything at every scale, from viral-cellular interactions to human infection dynamics and disease to why animal models aren’t people to transmission in different ecological and social contexts to elimation strategy to field epidemiology to human foibles and competing needs and ego and bureaucracy and struggles for power, influence, and money to global health politics and colonialism and post-colonialism and oh I’m getting distracted. Specifically, poliovirus is interesting in this case because, as a pathogen that is often transmistted by the fecal-oral route, naturalistic doses can vary by at least four orders of magnitude as a function of sanitation, and so the epidemiological concept of “being immune” depends a lot on where you live. (Read this for more.) We also have a live-attenuated vaccine that we can use to probe susceptibility to infection across the whole range of immune responses, and we have a history of being terrified of it in the rich world during the most scientifically-optimistic period in human history and an eradication program that makes all this variation worth caring about.

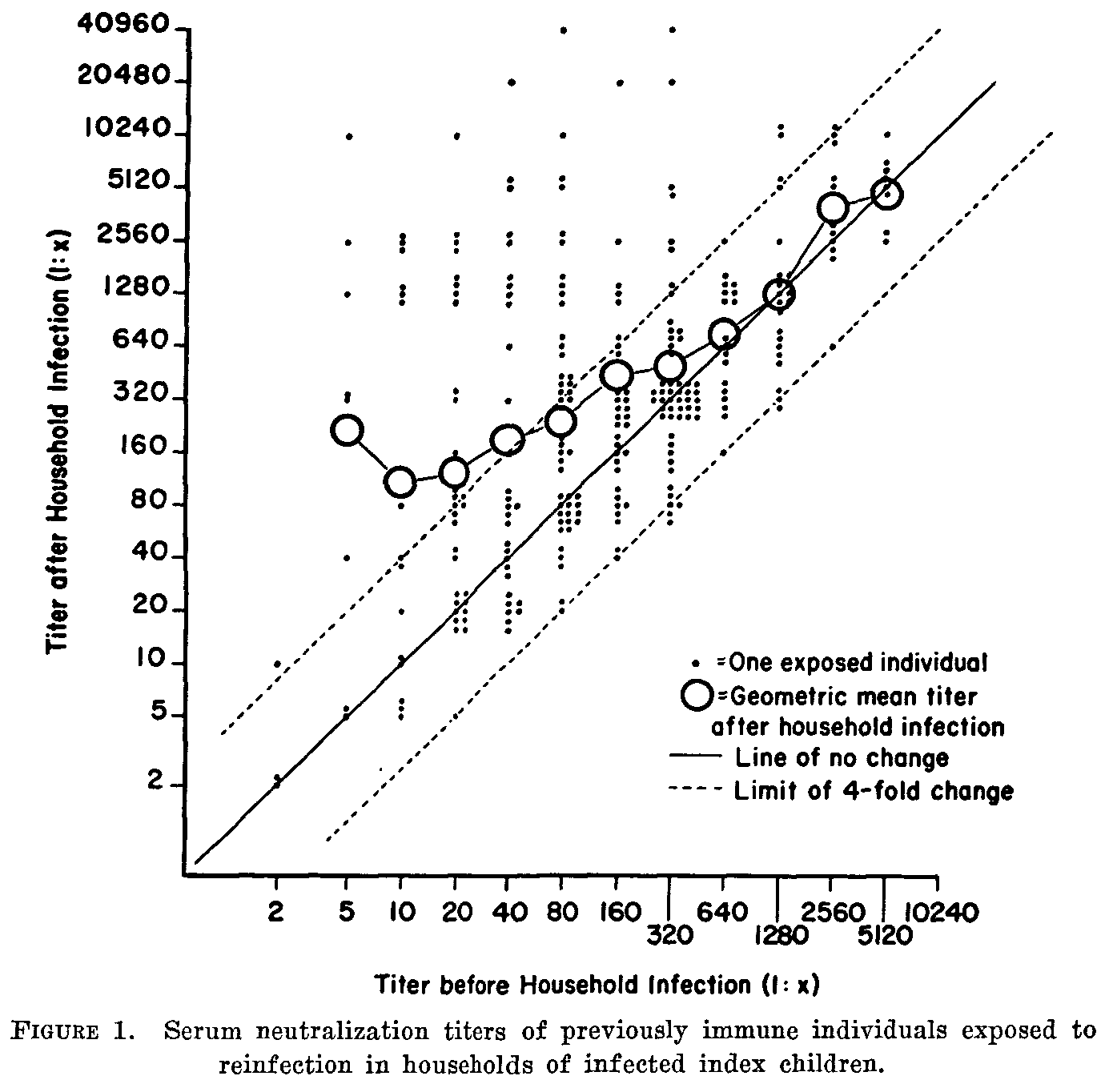

So anyway, back in the mid-1950s (a time when polio was important to rich people and scientific labor was cheap), Gelfand and co studied the heck out of a population in Louisiana with endemic polio. As part of that series of studies, they collected longitudinal blood samples roughly every 45 days from a few hundred people of all ages for three years. During this time, they observed over a hundred natural infections and studied pre- and post-infection antibody titer data, and generated this awesome figure in this paper1 that tells us everything we need to know about neutralizing antibody response after poliovirus infection.

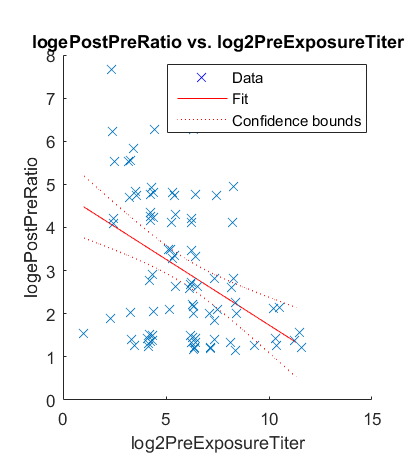

Back in the beforetimes, I was modeling poliovirus transmission across all ages to understand how it would change with changing vaccination policy, so we needed model of boosting that spanned all immune states. My collaborator, Wes Wong (now HSPH), did the annoying work of digitizing this figure into a CSV to fit a model to it.

When he looked at it in terms of the boosting multiplier, post-titer over pre-titer, he found that both the mean and the variance of the boost went to zero (the pre-post ratio went to one) at the same place and at approximately a neutralizing antibody titer of $2^{14}$.

I’ve forever worried that this is somehow an artifact of how titering assays are done, but I’ve never figured out a reason for how that could be. A nice thing about 1957 is labor was cheap and people didn’t know everything so they did terminal titrations on all of these and so there’s no censoring to deal with like you have in every antibody titer ever done today. And this model built on one very rich figure from 1957 has helped us successfully predict the outcome of vaccine trials and field studies conducted in the last 15 years, so it seems to be a real thing.2

So anyway, that’s cool! First, we have a model we can use to do transmission epidemiology like in this paper—the Day Science. But also, huh, there appears to be some biology about a power law relationship describing diminishing returns to boosting and the variance of antibody responses just sitting here. Something to note.

COVID and the Pfizer vaccine

So anyway, back in 2022, my colleague Dan Klein was trying to figure out how to update the immune response model in our covasim model to deal with bivalent vaccines and repeated immunization.3 At that point in time, we were modeling boosting as a constant multiplier on the previous titer, but that was kind of silly. Did we really believe you could just boost higher and higher forever? No! That’s silly–biology is full of resource constraints and I already knew polio didn’t work that way.

Since it was 2022 and I was exhausted and had a bunch of other stuff to do and we weren’t sure what we needed anyway, I just took a few data points from two papers about response: one pre-post point going from naive to one dose4 and two more pre-post points going from two doses to three and three to four. There was no data point from one dose to two because I didn’t recall at the time in 2022 a paper with the right pre-post timing. If you can remind me of one now, I’m happy to use it.

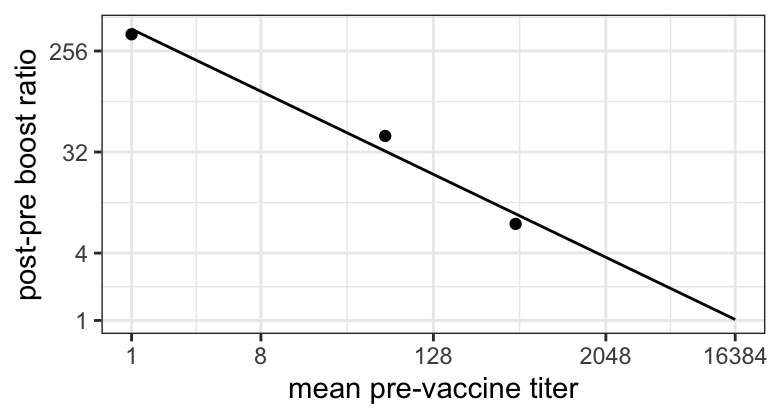

So anyway, this is Night Science, right? I’m just trying something out. So I throw three points for the mean responses into a regression, just like we threw a couple hundred individual level responses into two regressions for polio and what pops out for the boosting ratio?

Oh cool! That’s a power law again and wait, does the pre-post ratio hit one at $2^{14}$? IT DOES! AGAIN!

The precision here is, needless to say, very low, and Dan went in a different direction of covasim, informed by this but also by a bunch of careful Day Science to build a better immune model (that still isn’t great, as he’ll admit, but that’s why studying this stuff again two years later is part of my Day Science at the moment.) But here it is. A second coincidence for a maximum possible antibody titer.

RSV

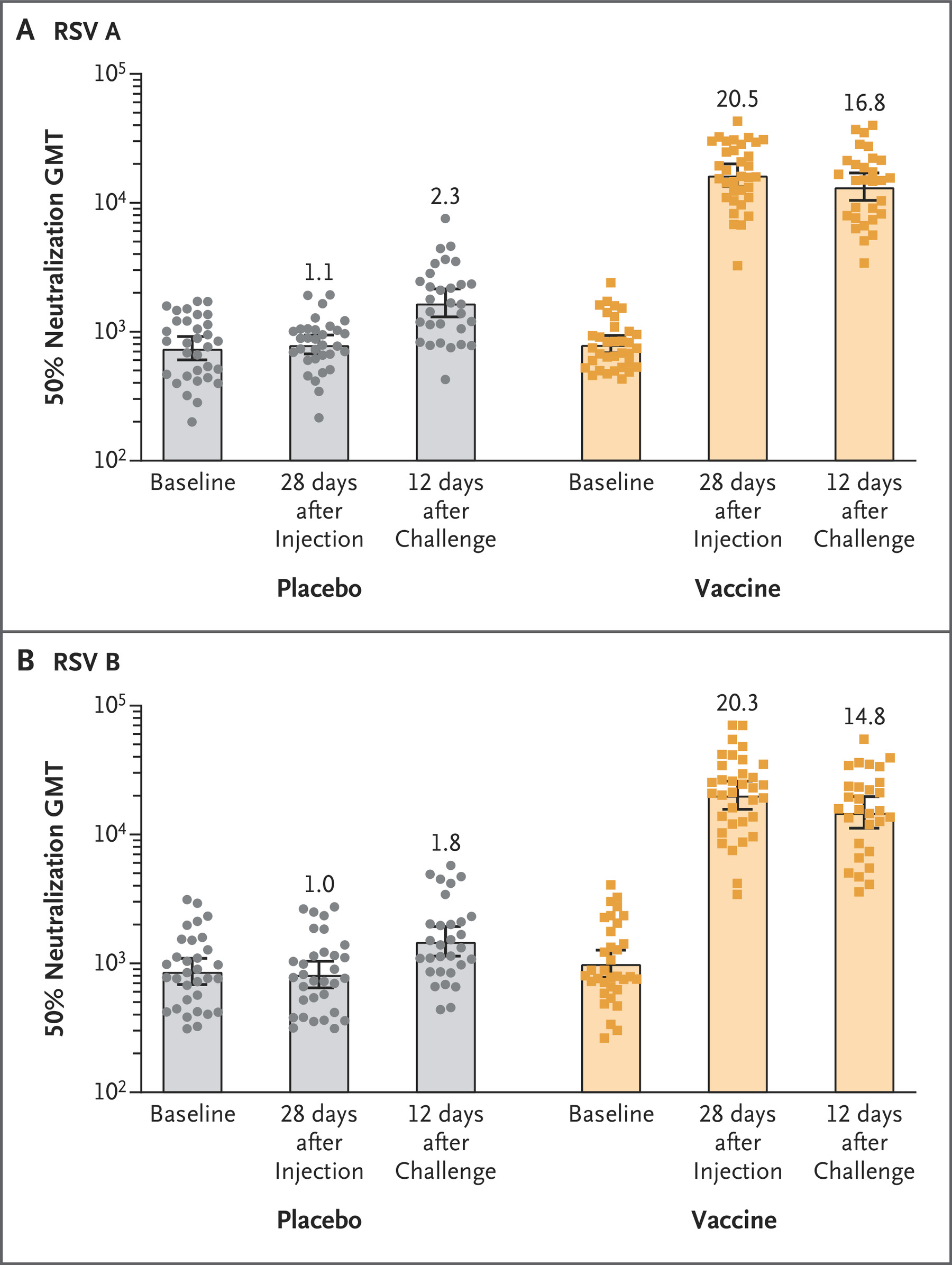

What do you see when you give a new RSV vaccine to adults who’ve surely had RSV repeatedly before? Peak titer of $10^{4.1}$, or roughly $2^{14}$.

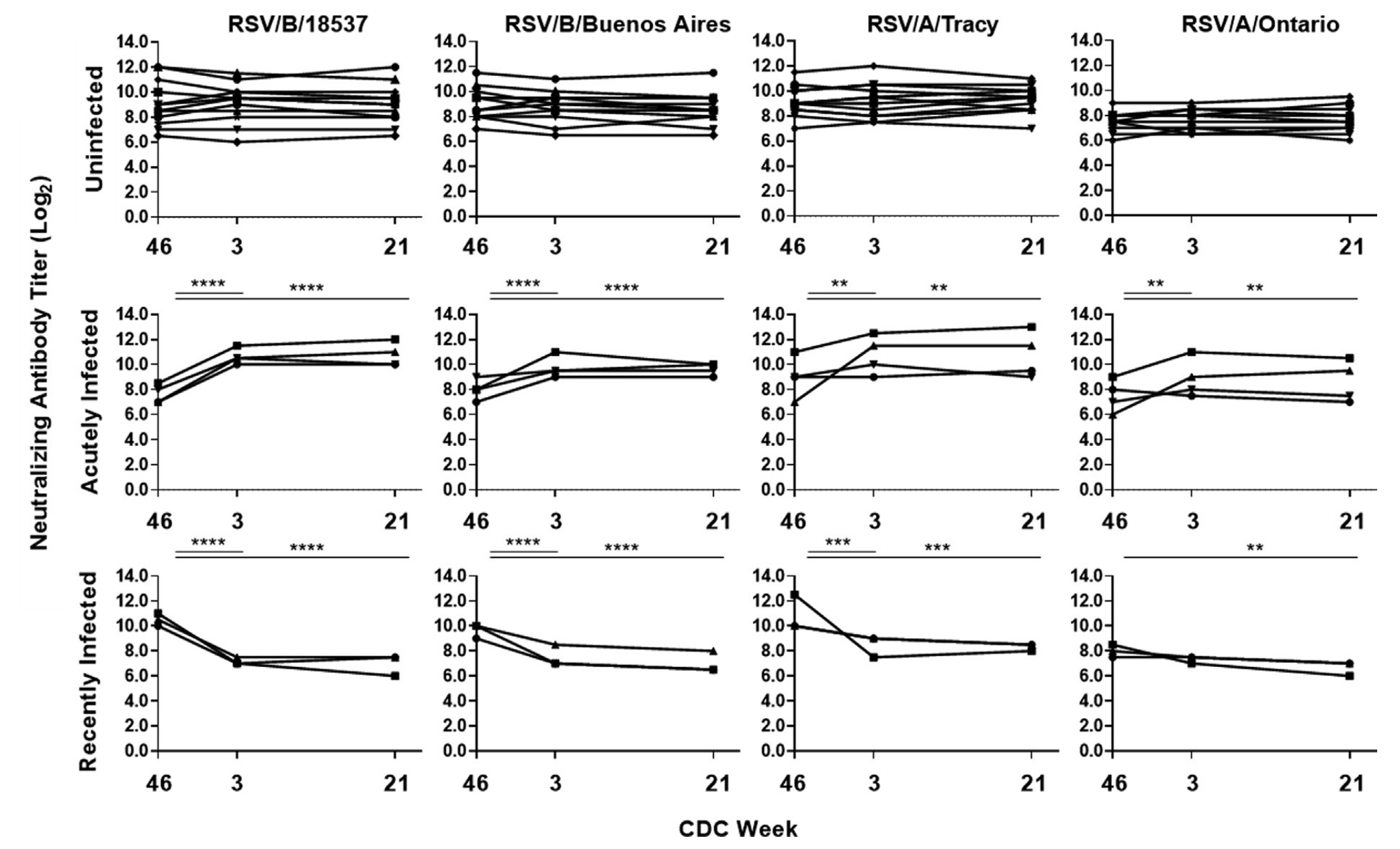

Oh, let’s look at some adults who recently got RSV and see what their neutralizing antibody titers are over time. What’s the highest number you see in this small sample? Is that $2^{13}$ish?

There’s others, like here’s a paper where you can see five-ish percent of people like have titers above the upper limit of $2^{12}$ where they stopped titering. And the funny thing is I can’t find the original study on pediatric waning where I first noticed RSV neutralizing titers peaked around $2^{14}$ that my colleague, Jamie Cohen, was showing me as she got into RSV modeling.

Oh yeah, and this amazingly hyper-vaccinated COVID case study!

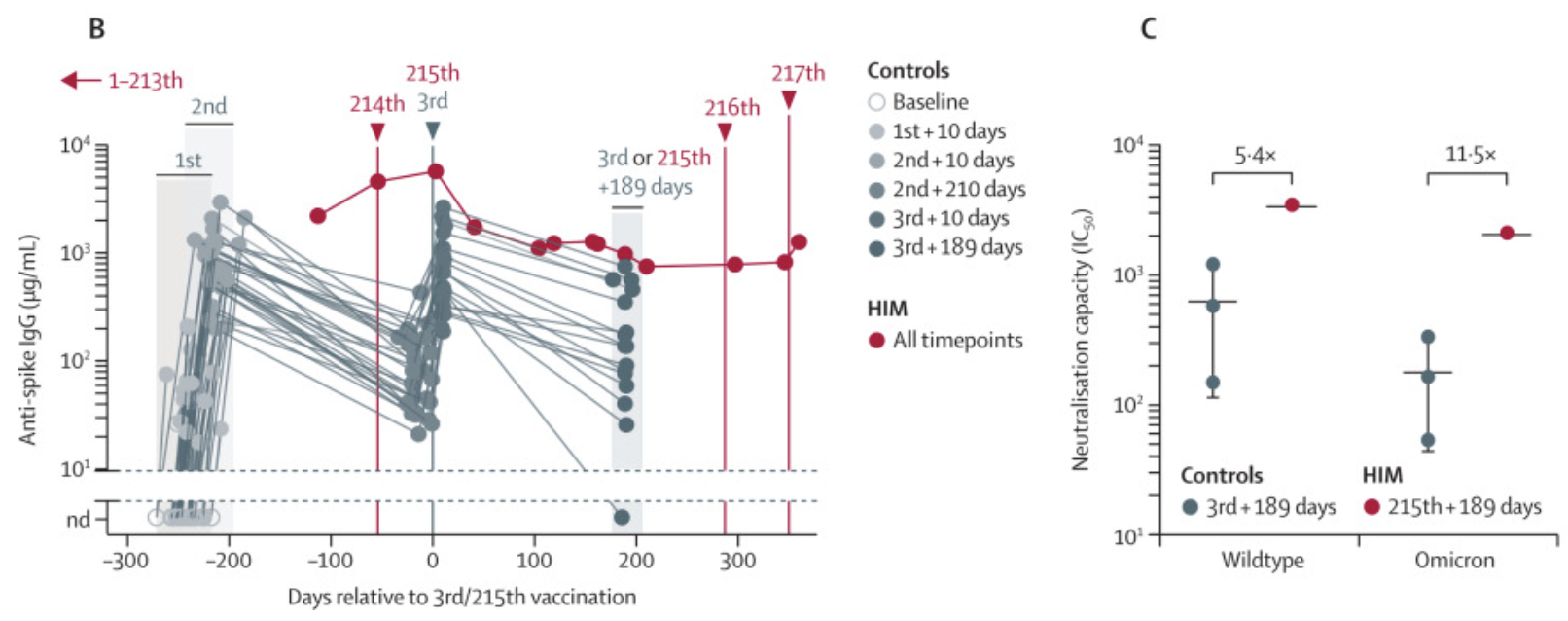

Oh yeah, you know what’s been in the news? This wild story! A German man got himself vaccinated for COVID 217 times! What was this gigavaxxed chad’s maximal antibody titer?

Well, we have to do a little thinking. In panel C, you can read off the graph that his wild-type titer 189 days after his 215th dose was 2,000. That wasn’t a peak antibody level as we can see in Panel B. The peak in panel B was a few days after that 215th dose. We can guess what his peak neutralizing titer would’ve been if we assume that IgG concentrations are proportional to neutralization titers, which is a noisy but linearly correct assumption. We can read of panel B that the IgG concentration at peak was about 5000 micrograms per milliliter, vs about 1000 at dose 215 plus 189 days. So we can guess his peak titer would’ve been 2000*5 = 10^4. Oh what’s that, $2^{13.3}$? No one else on earth got a close to measurable peak titer as this guy. HERE WE GO AGAIN.

What else?

I haven’t looked at any other viruses, but because it’s a hot topic right now, I’m putting this out there. Do you know anything that breaks this pattern? Particularly anything with observably higher neutralizing antibody titers, as lower is easy to come by (what you thought was a maximum wasn’t). If you do, please share!

How could this be? Isn’t antibody titer a relative unit? Relative to what?

I fear anyone who thinks about neutralizing antibody titers for a living will be pulling their hair out by now. Titers are a relative measure, with respect to some reference concentration and depends on the assay! How the hell could this be universal?

Well, here’s what I think needs to be true to survive that concern.

- The baseline reference concentration in humans is somehow set by the concentration of naive B-cells specific to the relevant antigens. As long as there is a roughly uniform distribution among the $10^9$ (IIRC, don’t quote me—comment with citation) different antigens covered by naive b-cells in the body, and there are a similar number of antigens presented at any one time across all viruses (talking order of magnitude here), then the baseline reference concentrations that later get boosted are about the same.

- All viruses are similarly immunogenic (again, order of magnitude). As in, you can’t reliably attract a helluva lot more memory b-cells to the party when you’re really highly immune. I’ll revisit this in the next post.

- This implicitly assumes we’re talking about people who aren’t absolutely fucked—people who don’t have exhausted immune systems due to uncontrolled HIV or a runaway immune reaction to severe COVID etc. We’re discussing peak titers in people maintaining homeostasis.

- The shape of the boosting curve—how we approach the peak for each pathogen and vaccine will depend on the details. How big is the dose? how immunogenic is each particle? but the conjecture is the peak is universal.

I think as long as these points are roughly true, then I think repeated immunization should lead to roughly the same peak antibody concentrations, and these will lead to roughly equivalent titers. So that’s what I think we’re talking about, peak concentration of actual molecules, with a reference standard given by the naive immune system.

And at that, let me know what you think! Especially if you think this is bonkers and can argue, even sloppily, why. Or if you think it’s great and you want add to it, let me know too!

Next time

In the next post, I’ll propose a very simple model for why neutralizing antibody titers max out. From that and using our polio model, I’ll show that susceptibility to infection and boosting response are both driven by the dynamics of poliovirus replication and neutralization at the cellular level. We’ll speculate a bit about what the simple model tells us about how the $2^{14}$ conjecture is probably a little bit wrong, from one virus to another and one vaccine formulation to another, but probably not too wrong. Until then!

Next post in the immunity theory series

For attribution, please cite this work as:

Famulare (2024, Mar 7). Conjecture---the maximimum possible neutralizing antibody titer. Retrieved from https://famulare.github.io/2024/03/07/Conjecture-the-maximum-possible-neutralizing-antibody-titer.html.

-

with 50% female authors in 1957! ↩

-

and we independently confirmed a statistically identical fit in a much more convoluted and model-dependent way by looking at viral shedding after vaccine challenge in kids of different ages in India. ↩

-

(My original question was could we predict the neutralizing antibody response against omicron BA.1/2 from a first dose of the bivalent vaccine in previously-immunized people by assuming it was half boosting cross-reactive wild-type antibodies and half starting a new response with omicron-specific antibodies. And the last line of my script says

# holy shirtballs, it works!but that’s a story for another day.) ↩ -

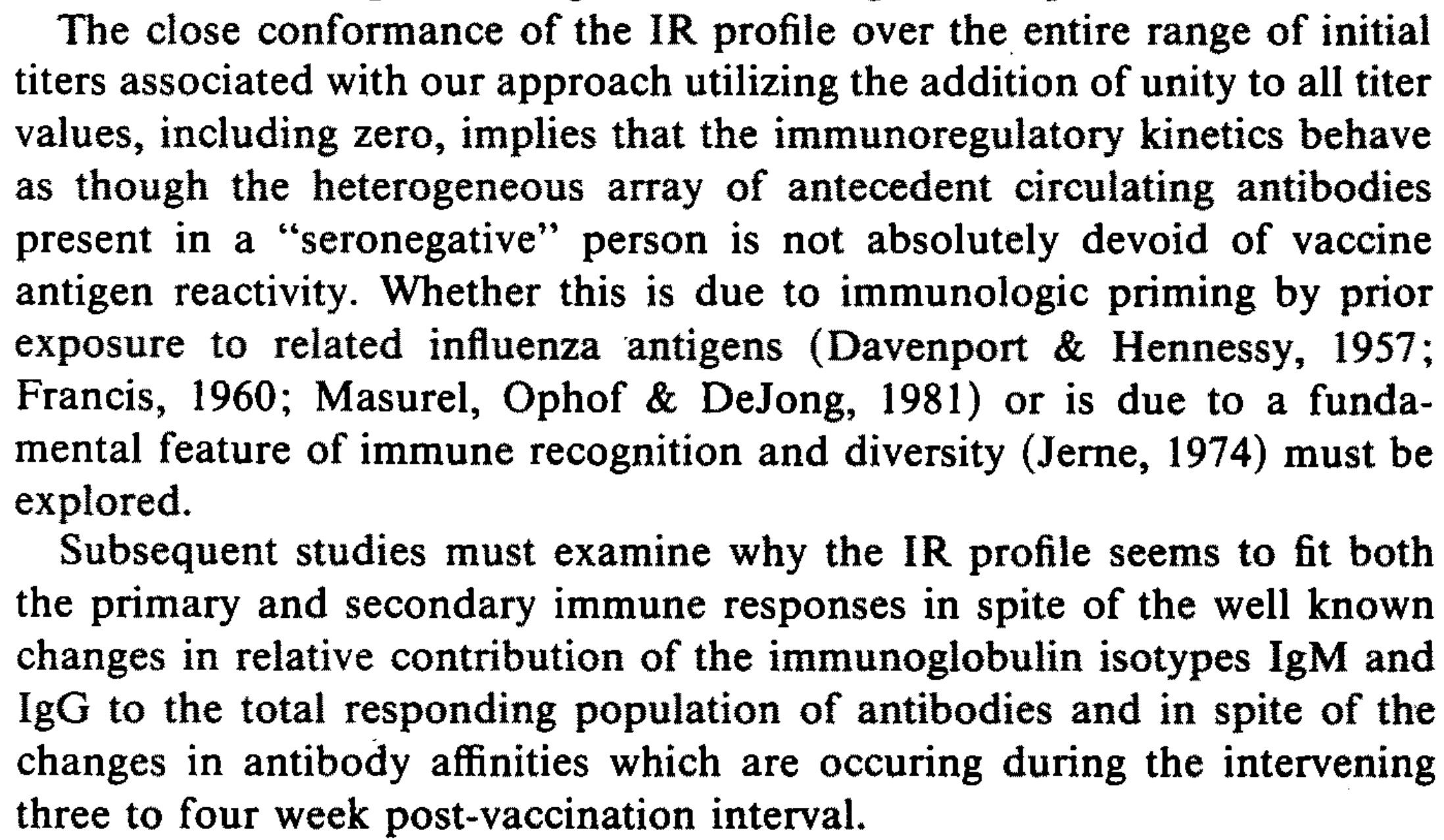

“You keep saying “boosting.” But the first data point is a primary response, right? What do you mean by boosting?” Funny right? One feature of the polio model and this COVID model is that it spans the entire range of neutralizing antibody responses with a single, two-parameter equation. Not shown here is it correctly predicts polio vaccine responses after the first dose. This model shows a continuous relationship, without any evidence for different mechanisms underneath. What this says to me is that the immune system is solving one math problem—how to boost in response to a bolus of antigen across the entire range of necessary (and possible!) immunity—with multiple systems (naive immunity and priming, creation of memory, then memory responses). The math problem biology needs to solve is often much simpler than how evolution cobbled together a way to solve it, but that’s a story for another day. Edit: March 22, 2024. I’m not the first to go down this road! Here’s a very relevant passage from this very relevant paper from 1984!

↩

↩